Hello CEOs, Presidents, and CXOs. Hello people in positions of authority to make far-reaching decisions. Now think of something interesting related to your business. You have it in your mind now? See it? See how you’d like to solve it? OK. Now, is that thing important? Of course it is!

Maybe it is. Is it?

Make sure you get it right, because the costs of flubbing this can be high.

You don’t want to miss the big thing that ends up really mattering. In the very least, you want to be in a position to handle the unknowable big thing that ends up really mattering. If you’ve been through this before, then you know that you don’t want it happening again. Getting the important things right matters big time.

Interesting vs. important. Is this just semantics?

This isn’t word play. Important things aren’t necessarily the most interesting things to you. And this isn’t nearly as obvious as you might think it is.

Or maybe it seems like I’m breeding doubt where confidence is needed. A leader has to trust his own judgment, or that means he lacks confidence, and we all know good leadership stems from sound confidence. This is about improving your judgment and that is what breeds confidence. What’s really important?

The view from the high hill.

If you’re in the C-suite, you make decisions about where to allocate the team’s time and energy. It’s like standing on a tall hill, peering into the distance with a clear line of sight.

What’s the landscape like over there? What’s happening on the ground? What’s the weather, the wind direction, etc.? What looks interesting?

Since you’re on a high hill, you have a pretty good view. Quite likely, you have the best long view of anyone on the team, which makes the view feel true. Besides, somebody has to make a call and a business doesn’t work well with multiple visions competing with each other.

But what about your exec team leader standing on another high hill seeing a slightly different view of the surround? Might they see something different? They almost certainly will. Your customer too. Your board of directors. Etc.

Different views, different takes on interesting…different takes on important.

You may think, I see where you are going with this. I’ve seen management-by-committee. I’ve seen consensus decision making. They’re terrible! Everything takes forever and the decisions are watered down compromises that don’t provide us strong competitive advantage. And it’s maddening.

I agree!

Thankfully, I don’t prescribe that. This isn’t about compromise and middle ground. This is about being deeply informed when making your judgment calls. Also, if you are consensus-committed, then you might want to rethink that approach.

So no. No managing-by-committee around here.

You may also think about that time you took someone else’s advice and it didn’t go well. You remember with vivid pain and ferocity how you second-guessed your decision and regretted it. Never again, you swear! Never again will I subjugate my opinion to someone else because if I’m going to be accountable for the results of the decisions, these need to be my decisions.

You’re right!

The truth about human judgment.

Here’s the thing with decision making. No view is perfect, and you might be wrong about what’s important. I might be wrong about what’s important.

It’s really, really tempting to confuse the two—to believe that what we, as leaders, are attracted to thinking about is necessarily the most important thing to attend to (or worry about) for the good of the business. It’s hubris, really. A naturally occurring, self-congratulating very human tendency. It’s hard to know.

And yet…

I’m not sure where this certainty that we have a monopoly on truth comes from, but it sure seems baked into the human genome. And when you layer the power dynamics of an organization’s decision-making patterns on top of this probably-unwarranted-certainty, you end up with some pretty significant organizational biases. Most likely, your business suffers from systematic over- and under-valuation of the things most interesting to those who have the most organizational power.

Important and interesting. How do you tell them apart?

If everyone on your team thinks the same, that’s not good. There is real value in having thought diversity on your leadership team. It helps to have a team of people paying attention to their different sorts of interesting, that look different sorts of important. This thought diversity broadens your interesting/important landscape. That’s useful.

How do we know when something is important?

Things aren’t important in isolation. Just important implicitly—always, all the time, forever important just because. Importance is relative to a value, a desired outcome, a principle. It must be important FOR something or FOR some intended outcome.

If you can’t answer the question of important for _____ ? Then maybe it’s not important…maybe it’s just interesting. Which is a sort of important, but probably not the kind of important you are predisposed to imagine that it is.

What can happen if this tendency to confuse interesting for importance runs unchecked?

Strategic decisions are about setting direction and prioritizing the money, information, time, and energy of your business. How to best do this is a matter of judgment by leaders like you and the other readers of this blog. No leader, you included, wants to make decisions with huge blind spots. Do you like blind spots? Most people don’t like to be surprised. Do you like to be surprised?

We know perfect info that eliminates surprises and blind spots is impossible, but a practice of broadening the options results in better decision making. Better decision making means discovering the difference between important and interesting.

How do you do that?

Add decision making practices that reduce strategic blind spots.

Once you are open to the perspective that interesting doesn’t always mean important, there are lots of ways you can systematize getting better at making the distinction between interesting and important.

Thinking differently about how people decide, interact, and do business.

Let’s forgo out-of-the-box advice, because you can find that anywhere. To focus your solutions on the unique qualities of your business, we’ll start with laying some groundwork that you can then apply at your business. Part of the groundwork is understanding what we know about human nature and how it impacts your ability to make good decisions. If you want to innovate more—to succeed more—let’s address root causes of common dysfunction. Cognitive bias is a common dysfunction.

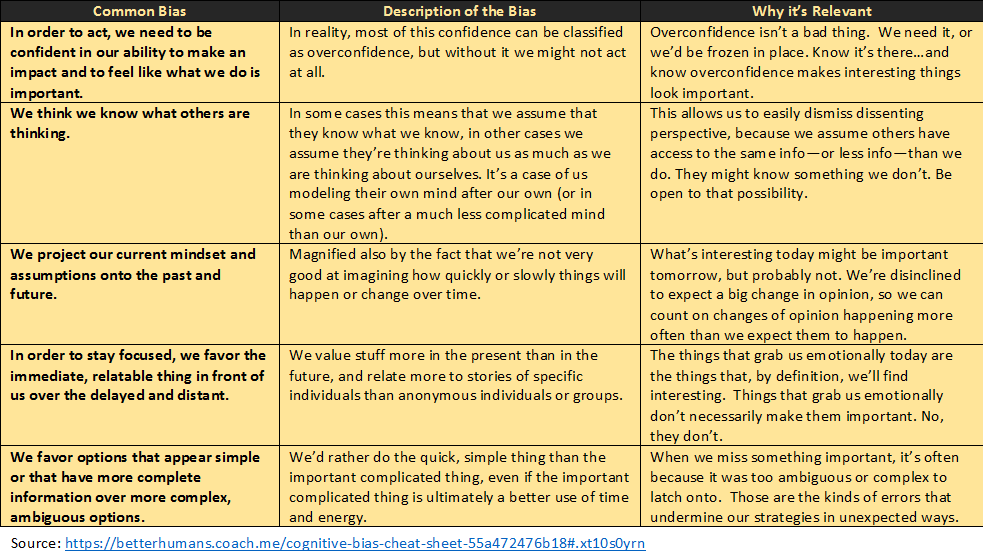

Common cognitive biases that encourage us to conflate important and interesting.

Let’s familiarize ourselves with some of the more relevant ones. Below is a chart with the bias, a brief description, and an explanation of why it’s relevant to our ability to distinguish interesting and important.

Your brain’s natural processing-fluency shortcut.

Cognitive biases are useful because they save us energy and time. Sometimes, however, this same energy-saving shortcut serves us to slow down and make sure we aren’t being had by false assumptions about what’s important.

How do we slow down?

Applying more science in your business’ operations.

Science is teaching us more about how the mind works both for us and against us in business. Science can also help us reduce the hold that our cognitive biases have on us and get the important vs. interesting distinction more accurate. Here are some smart scientists with some good suggestions.

Let’s start here with some thoughts from two experts from their interview published in McKinsey Quarterly. Nobel Prize winner, Daniel Kahneman, notable for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making, advises us as follows to improve our strategic decision making.

[pullquote align=”normal” cite=”Daniel Kahneman”]My single piece of advice would be to improve the quality of meetings—that seems pretty strategic to improving the quality of decision making. [/pullquote]

You probably have meetings. And you probably already have the people and the tools you need to get better at telling the difference between interesting and important. What if you could improve the quality of the decision-making during meetings just a little bit, what would that mean for your business? Have better meetings.

Here’s what Gary Klein has to say about that.

[pullquote align=”normal” cite=”Gary Klein”]What concerns me is the tendency to marginalize people who disagree with you at meetings. There’s too much intolerance for challenge. As a leader, you can say the right things—for instance, everybody should share their opinions. But people are too smart to do that, because it’s risky. So when people raise an idea that doesn’t make sense to you as a leader, rather than ask what’s wrong with them, you should be curious about why they’re taking the position. Curiosity is a counterforce for contempt when people are making unpopular statements.[/pullquote]

The lesson here is in making it safe to share challenges to what the biggest-title-in-the-room believes is important. Many leadership teams do great work encouraging constructive debates. But there are always, always off-limits topics and the people that don’t have the biggest-title-in-the-room will sniff those out in a hurry. At least, I’ve never come across a leadership team that completely removed the risk of marginalization.

I’m not suggesting you aim for that, because it might not be humanly possible. What you want to think about is establishing alternative ways to vet the important vs. interesting question, and that starts with listening well.

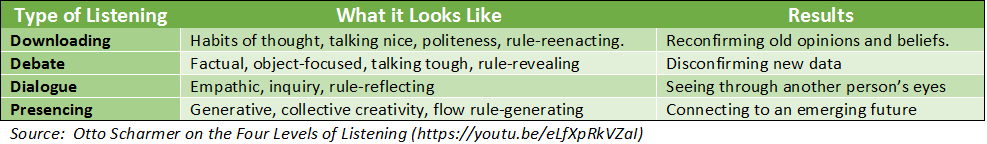

Listening well in meetings.

There are different kinds of listening and they aren’t equal in their ability to help you discern interesting and important. How can you tell which kind of listening you are doing? Otto Scharmer describes four levels of listening in this video that I convey in the chart below.

Which type of listening do you think enables you to best discern the difference between interesting and important? Now consider how to prompt you and your colleagues to listen at the right level for the decision at hand.

Build explicit experimentation into how you operate.

The scientific method was developed to minimize the effect that bias and preconceived notions have on learning how the universe works. As a business leader, you can use some of the science tricks to minimize the effect of bias and preconceived notions in making sound business decisions. We’ll discuss a few options to get you started on the path to better clarity.

Bob Nease, in an article on FastCompany website, suggests building in experimentation into how you do things. Because you can’t eliminate bias about what’s important vs. what’s just interesting, you should assume that you are regularly making that error and add in tests to catch these decisions before, during, or even after implementation. Nease provides the example below to illustrate.

[pullquote align=”normal” cite=”Bob Nease”]For example, suppose you have a formal process for ranking candidates that you’re considering hiring. You might periodically, and at random, hire the candidate ranked second or third. This approach allows you to test whether your ranking algorithm is actually working; without it, you’ll never really know.[/pullquote]

What are the different ways you might bake regular testing into your business decision processes? Think through how you can test whether you’ve uncovered what’s important and worth focusing on. Consider how you might keep tabs on what you thought wasn’t important.

Really smart people seek out disconfirmation instead of confirmation.

Confirmation bias is a bugger. It will get you every time if you start with a theory, buy into the theory, and then go looking for evidence. That’s why the deepest experts, the Nobel Prize winner types, they put their energy into coming up with ways to disconfirm their theory. It’s more rigorous. It’s a faster path to truth.

Here’s what Joseph Rowlands from Rebirth of Reason has to say about the importance of seeking disconfirmation.

[pullquote align;”normal” cite=”Joseph Rowland”]For a theory to be tested well, you have to look for disconfirming evidence. You can’t just look for evidence that supports your initial impressions. You have to figure out what wouldn’t meet those expectations and look for the evidence that would disconfirm the theory…(T)his is all tied to Karl Popper’s view that real science must be falsifiable. He formulated this idea when he notices some popular “scientific” theories of his day were compatible with any possible outcome.[/pullquote]

Here’s another related point from Gary Klein in an interview published in McKinsey Quarterly.

[pullquote align;”normal” cite=”Gary Klein”]It depends on what you mean by “trust.” If you mean, “My gut feeling is telling me this; therefore I can act on it and I don’t have to worry,” we say you should never trust your gut. You need to take your gut feeling as an important data point, but then you have to consciously and deliberately evaluate it, to see if it makes sense in this context. You need strategies that help rule things out. That’s the opposite of saying, “This is what my gut is telling me; let me gather information to confirm it.”[/pullquote]

This idea ties back to experimentation in your decision processes. Before you implement a big strategic decision, think through what would disconfirm your assumptions about this being the best course of action. Then think through how you can gather that information before, during, or after implementation.

The role of measurement in decision science.

With all this talk about adding science to decision making, we should tackle the issue of measurement. Science and measurement seem like concepts that belong inviolably together. Inseparable.

Can you apply science without measurement?

Yes. When we talk about decision science, we’re talking about process. We’re talking about adding rigor to the process to remove the influence of bias and preconceived notions. It’s easy to get caught up in the idea that if something is hard to measure, then it’s harder to disconfirm, which must mean it’s not important. It can only ever be interesting if you can’t measure it.

Does measurability actually determine importance?

Not according to Dr. Edwards Deming, despite the frequency at which people take his quote out of context to suggest otherwise. Here’s what he really said.

[pullquote align;”normal” cite=”Edward Deming”]It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it – a costly myth.[/pullquote]

Dr. Deming did very much believe in the value of using data to help improve the management of the organization. But he also knew that it wasn’t the whole picture. There are many things that cannot be measured and still must be managed. And there are many things that cannot be measured and managers must still make decisions about.

So, no, whether you can measure something has no bearing on whether it’s either important or interesting. Don’t make that error.

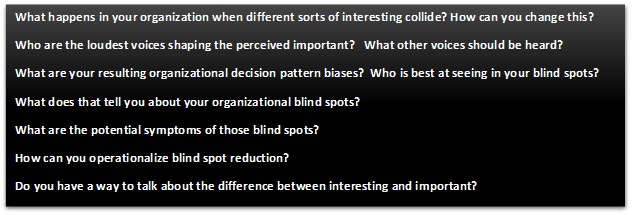

Ask hard questions about your decision-making practices.

We spend most of our time working in our business and very little working on our business. If you are committed to reducing the errors you make due to conflating things that are interesting with things that are important, then you have some work to do on your business. To get you started, here are some examples of the kinds of questions to ask yourself to help you discern just-interesting from also-important.

Taking my own medicine.

What do you think? Is this an important topic? Or am I just modeling the problem and prescribing solutions to solve a problem that I find interesting?

Let’s revisit the suggestions discussed throughout this post to get a bead on that.

- Important for ___________?

- Know your biases.

- Listen well in meetings.

- Explicitly experiment and test hypotheses.

- Seek disconfirmation of pet theories.

- Use measurement, but not in isolation

- Ask hard questions.

This is an interesting topic to me, I readily admit that. I believe it’s important because even if only one person improves their decision-making in a useful way, then that’s worthwhile. When things are actually important, they have an impact on the customers, employees, and the financials.

How can I disconfirm this is true? You, reader, will let me know if you the suggestions fail to improve the quality of your business’ decision making. I will keep listening with presence to the smart and capable leaders I know to keep learning. I will test these hypotheses out in real-life scenarios and fine tune them. I will use measurement and data, but not let it replace holistic judgment.

What you should remember about the difference between interesting and important.

You’re a business leader. Because you are human, you will have a hard time telling the difference between what’s interesting and what’s important. We all do. Because you are a business leader, you are responsible for the health and results of the business.

Leaders, I leave you with this. You will always know what’s interesting to you. Flawlessly. On the contrary, you won’t always know what’s important. You can get better at it though. It’s going to take some work, but it’s doable.